Esther Freeman, MD, PhD, was on the frontlines of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2003 when she decided to pursue dermatology. At the time, she was working with Partners in Health (PIH) in Lesotho, a landlocked country in South Africa, treating HIV and AIDS patients with whatever supplies were on hand.

“There were a lot of people living with HIV in Lesotho, but at that time, very limited antiretroviral therapy,” recalls Dr. Freeman, who is now the inaugural L’Oréal Dermatological Beauty / CeraVe Endowed Chair in Global Health Dermatology, Director of Global Health Dermatology at Mass General, and an Associate Professor of Dermatology at Harvard Medical School, in Boston, MA. “Working in remote and rural villages, we didn’t

have the ability to get lab tests or diagnostics, and what I realized is that we were actually able to do a lot with our eyes.”

She recalls how some patients would slowly unwrap their clothes and reveal purple lesions on their skin that were Kaposi’s sarcoma. “It would be immediately apparent that the person had full-blown AIDS and needed therapy, immediately.”

Dr. Freeman quickly learned to stage HIV disease based on physical exam and keen observation. “We knew based on point-of-care testing whether they were HIV-positive or negative, but we didn’t necessarily have their CD-4 count or their viral load. Their skin was telling us a story,” she says.

“These are patients that deserve our care, dignity, and the ability to help get healthcare the same way that my mom does here in the Northeast of the United States, so that was how I was inspired to become a dermatologist.”

When she returned from Africa, Dr. Freeman, who had already received an MSc and a PhD in infectious disease epidemiology as a British Marshall Scholar at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in

London, U.K., pursued a medical degree at Harvard Medical School. In addition, she received a Diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (DTM&H) from the Gorgas Memorial Institute in Peru.

She currently treats general dermatology and infectious disease patients at Mass General, teaches dermatology at Harvard, runs the Freeman Global Health Dermatology Epidemiology Lab, and is active in the International League of Dermatological Societies (ILDS).

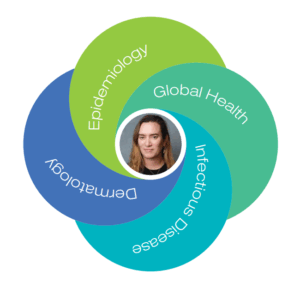

She now sees herself firmly ensconced in the middle of four overlapping squares in a Venn diagram: epidemiology, global health, infectious disease, and dermatology.

“I’m that little, tiny square in the middle where all of those things overlap,” she says.

Making a Difference

Several years ago, Dr. Freeman co-founded the International Alliance for Global Health Dermatology (GLODERM). This group connects dermatologists, trainees, and healthcare professionals worldwide to promote skin health

in resource-limited communities. Soon after, GLODERM joined forces with the ILDS, an umbrella organization for professional dermatology groups of all sizes.

“It’s been a really wonderful partnership, and we are now firmly part of ILDS,” says Dr. Freeman, who serves as the Vice Chair of the International Foundation for Dermatology, the philanthropic arm of the ILDS.

GLODERM – and its reach — has grown considerably since its inception. “We started as a small group of 10 leaders around the world interested in creating community and building collaboration across global health and dermatology,” she says. “We now have more than 3,000 members from over 60 different countries, and we’re in every continent except Antarctica.”

GLODERM has also started to support new residency training programs in low-resource areas to increase the dermatology footprint in these countries.

The group offers a mentorship program to help train and support future leaders in dermatology from under-resourced nations. “So far, we’ve trained 29 emerging leaders from resource-limited countries from 27 different countries.”

These leaders see thousands of patients every year and are able to train additional healthcare workers within their communities. “It’s a ripple effect,” she says. “If you find and empower the right individuals, it can really make a huge impact even if you’re only training a smaller number of individuals per year.”

One of the programs’ mentees has gone back home to Burundi, in central Africa, where she’s the sixth-ever dermatologist and has created an albinism outreach program for the thousands of people living with albinism in Burundi.

These yearlong mentorships are intensive, one-on-one experiences. “That’s probably been one of the most rewarding experiences of my entire career,” she says.

Dr. Freeman is so inspired by her mentees that she wears a necklace with medallions from their countries right next to charms with her kids’ initials. “I literally wear my kids and my mentee’s countries around my neck on a daily basis.”

Claire Fuller, MA, FRCP, Chair of the International Foundation for Dermatology (IFD) and who represents the IFD on the Executive Board of the ILDS, worked with Dr. Freeman to launch GLODERM. “It’s been a ball seeing this initiative flourish, and I’ve loved her style of developing what’s required as the need reveals itself,” says Fuller. “This nimble and flexible approach to getting things done is a crucial skill for global health, and she’s got it in spades.”

But there’s even more that Dr. Freeman brings to the table, says Fuller. “It’s her attention to personal relationship cultivation that shines out to me most. Her care and attention to those she professionally encounters illustrates the strength of her personal integrity.”

More Than Just Infectious Skin Disease

Now, Dr. Freeman is working on the Global Access to Skin Health Observatory (Skin Observatory) study, a collaboration between the ILDS and L’Oreal Dermatological Beauty. This study aims to quantify and address the lack of comprehensive global data on the distribution of dermatologists and barriers to dermatologic care across all 194 WHO member state countries.

Skin cancer and infectious diseases of the skin such as tinea are prevalent in many of these underserved countries.

“Severe atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, even lupus are conditions that we really see the world over. We all know there is a lot of infectious disease, but we have to remember that inflammatory skin disease is actually also a huge problem worldwide.”

Dr. Esther Freeman

When a person has a skin disease, everybody can see it.

“Skin disease is incredibly stigmatizing, but it also can be a window into how people’s immune system is functioning and be a window into bringing them into healthcare.”

Dr. Esther Freeman

People are much more likely to come in for something they see and others see.

“We need to have people who are trained and available and the medications available to treat these patients,” she says, noting that it might be pharmacists, nurses, or other frontline healthcare workers, not necessarily dermatologists, who are providing such care in low-resource settings.

And Dr. Freeman, her mentees, and colleagues here and abroad won’t stop until such care is readily available around the globe.