Steven Hainsworth, BAppSci, MMedSc, with Cheryl Guttman Krader

For almost three decades, the allylamine antifungal drug terbinafine has been the first-line drug for treating dermatophyte infections, and it remains a reliable choice. However, dermatologists should be aware that terbinafine resistance is a real phenomenon that appears to be on the rise and spreading, said Steven Hainsworth, DPM.

“An epidemic of treatment-refractory dermatophytoses in India has raised concern about terbinafine resistance, and the list of countries where terbinafine resistance has been found is growing,” said Dr. Hainsworth, a clinical podiatrist and research scientist from Melbourne, Australia. “Because the estimated incidence of terbinafine resistance appears to be low in countries other than India, terbinafine is still a very useful antifungal agent. Clinicians should remember that if the resistance rate is 2%, that means 98% of isolates are still susceptible.”

“Because it is uncertain whether the low incidence of terbinafine resistance outside of India is real or reflects a lack of research, this is a situation that needs to be monitored.”

A brief history

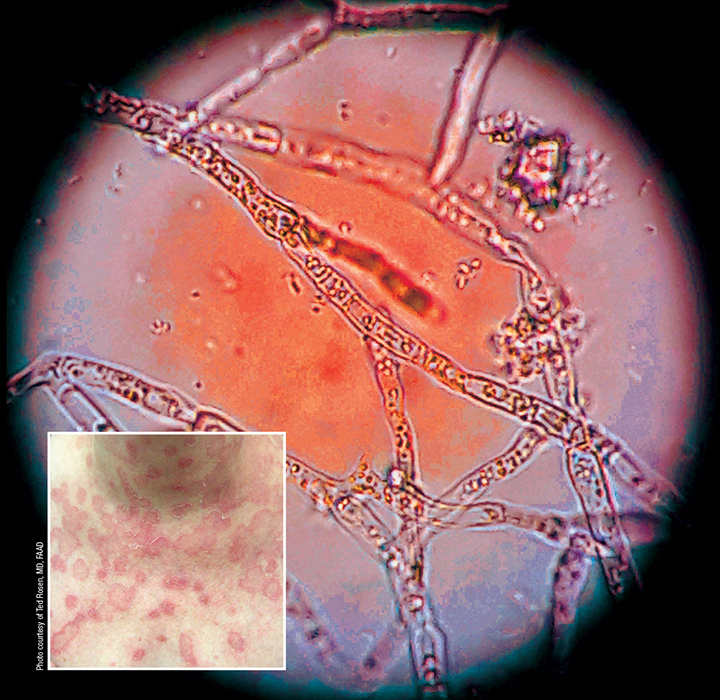

The first documented case of a terbinafine-resistant dermatophyte was identified in the US in 2003 and involved a Trichophyton rubrum isolate from a patient with a toenail infection.1 Resistance of the strain to other antifungal agents (tolciclate, butenafine, naftifine, and tolnaftate) that act by inhibiting the squalene epoxidase gene (SQLE) indicated that the mechanism for resistance was related to this gene. Subsequent research identified clinical isolates harboring additional single-point mutations in the gene.2-5 These point mutations resulted in single amino acid substitutions at the site of terbinafine binding. As of 2019, 6 mutations in the SQLE gene leading to resistance of T. rubrum and 2 mutations associated with T. interdigitale resistance have been identified.

Dr. Hainsworth explained that the terbinafine mode of antifungal activity is mediated by inhibiting the production of squalene oxidase by the SQLE gene. This inhibition results in squalene accumulation and also interferes with ergosterol production. Excess squalene is toxic to the cell and causes cell lysis while the lack of ergosterol, which is an essential cell membrane component, results in loss of cell membrane integrity (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Terbinafine mode of action

“Mechanisms for resistance other than these point mutations are thought to exist, and several have been proposed.6 Further investigation of these possible causes is needed. The current lack of knowledge in this area, however, is a limiting factor when talking about terbinafine resistance,” Dr. Hainsworth said.

The problem of terbinafine resistance has gained prominence in the last decade because of an epidemic of treatment-resistant severe dermatophyte infections in India, which is ongoing.7,8 The causative organism was initially thought to be an internal transcribed spacer (ITS) genotype of T. mentagrophytes or T. interdigitale and became known as the “Indian ITS genotype”: T. mentagrophytes Type VIII. Subsequent testing, however, identified the pathogen as a separate species, a new recently described anthropophilic species within the T. mentagrophytes complex named T. indotineae.9,10

“The terbinafine resistance rate among this genotype may be as high as 75%, and the lesions associated with these infections are large and can be very severe with erosions. These isolates can demonstrate an extremely high terbinafine resistance,” said Dr. Hainsworth. 11

As of 2020, T. indotineae had been detected only in Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and Australasia, but it has been said that those locations may just be the tip of the iceberg.12

“Although there are no reports yet of terbinafine-resistant T. indotineae from North America, South America, or Africa, that may just be because those areas are sparsely studied for resistance when it comes to dermatophytes. A careful eye needs to be kept on immigrants and travelers from the Indian subcontinent and surrounds for the emergence of the species T. indotineae,” Dr. Hainsworth said.

Identifying terbinafine resistance

Numerous explanations exist for cases of terbinafine treatment failure, particularly involving nail infections. Possibilities aside from terbinafine resistance include the fact that the nail is a natural barrier to antifungal drug penetration. In addition, lack of response may be due to insufficient treatment duration, environmental reinfection, coexistent tinea pedis creating a reinfection cycle, mixed fungal infection, biofilm that is protecting the dermatophyte from the drug, or the presence of thicker-walled arthrospores, which are difficult to eradicate with terbinafine at clinically achievable concentrations.

“Terbinafine resistance should be considered in cases of treatment failure. Currently, however, there is no way to know if it is the actual cause. Resistance needs to be tested for scientifically, and this will require access to a new straightforward laboratory method to screen or test for terbinafine resistance.”

“Such a test that would give information on the effectiveness of terbinafine for a particular case, providing meaningful feedback for guiding therapeutic selection. Or, if the organism is found to be susceptible in a refractory case, it could allow clinicians to explore other factors that might explain the treatment failure. In addition, a straightforward screening method would be useful for researchers, who could identify which isolates are resistant and warrant further study. This would save valuable time and resources,” he added.

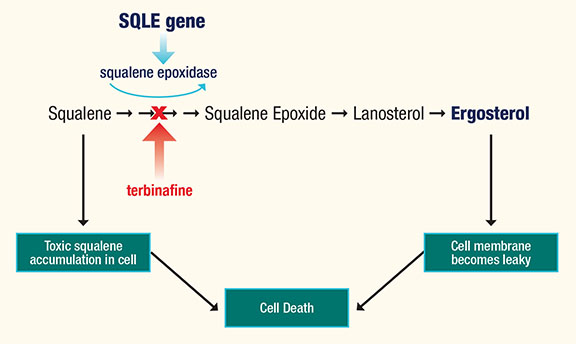

Dr. Hainsworth has developed a simple screening method that is performed using common laboratory supplies (agar plates) at the time of early culture growth. Samples are plated onto Petri dishes containing solid potato dextrose agar alone or with terbinafine in increasing concentrations. Organism growth on any plate containing terbinafine at these concentrations is interpreted as a sign of resistance (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A screening method performed at the time of early culture

“Instead of laboratories reporting genus/species, perhaps it would be more informative to report genus/terbinafine-susceptible or terbinafine-resistant. If the lab report shows resistance, then perhaps an alternative antifungal medication should be used,” Dr. Hainsworth said.

While the agar screening method could be developed for implementation soon for non-molecular laboratories and is a good starting point to screen for terbinafine resistance, molecular assays that detect point mutations in the SQLE gene would be better and might even become a point-of-care diagnostic test. These assays could be performed on cultures or ideally applied directly to infected skin or nail samples, thereby eliminating the need for cultures.

“Especially in recalcitrant severe cases, it would be particularly helpful to have a molecular method for detecting T. indotineae because it is difficult to distinguish morphologically from other species of the T. mentagrophytes complex. The technology exists but still needs to be developed. When we become aware of other mechanisms for terbinafine resistance, perhaps they might also be identified using assays for molecular markers,” said Dr. Hainsworth.

Managing resistance

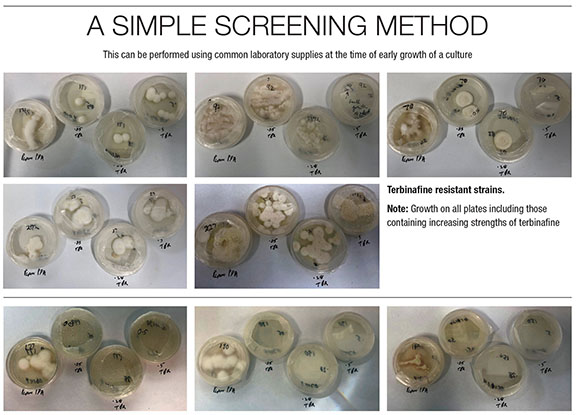

If terbinafine resistance is suspected in a treatment-refractory dermatophyte infection, Dr. Hainsworth recommended switching treatment to the azoles such as itraconazole and fluconazole for oral treatment, and luliconazole for topical treatment. In nail infections in which arthrospores are common, the nail overburden should be removed (Figure 3) to reduce the arthrospore count, and oral treatment should be supplemented with topical treatment to increase the terbinafine concentration in the nail and nail bed.

“It is not possible to raise the dose of oral terbinafine high enough to be effective against arthrospores because the concentration of terbinafine needed to kill them is 1000-fold higher than that needed to eradicate hyphae,” Dr. Hainsworth said.13

Figure 3. Thickening of the nail, common in chronic advanced cases. Note the coexistence of tinea pedis.

References

1. Mukherjee PK, Leidich SD, Isham N, et al. Clinical Trichophyton rubrum strain exhibiting primary resistance to terbinafine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003 Jan;47(1):82-6.

2. Osborne CS, Leitner I, Favre B, Ryder NS. Amino acid substitution in Trichophyton rubrum squalene epoxidase associated with resistance to terbinafine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(7):2840-4.

3. Osborne CS, Leitner I, Hofbauer B, et al. Biological, biochemical, and molecular characterization of a new clinical Trichophyton rubrum isolate resistant to terbinafine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(6):2234-2236.

4. Yamada T, Maeda M, Alshahni MM, et al. Terbinafine resistance of Trichophyton clinical isolates caused by specific point mutations in the squalene epoxidase gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(7):e00115-17.

5. Hsieh A, Quenan S, Riat A, Toutous-Trellu L, Fontao L. A new mutation in the SQLE gene of Trichophyton mentagrophytes associated to terbinafine resistance in a couple with disseminated tinea corporis. J Mycol Med. 2019;29(4):352-355.

6. Shaw D, Singh S, Dogra S, et al. MIC and upper limit of wild-type distribution for 13 antifungal agents against a Trichophyton mentagrophytes-Trichophyton interdigitale complex of Indian origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64(4):e01964-19.

7. Bishnoi A, Vinay K, Dogra S. Emergence of recalcitrant dermatophytosis in India. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2018;18(3):250-1.

8. Ebert A, Monod M, Salamin K, et al. Alarming India-wide phenomenon of antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: A multicentre study. Mycoses. 2020;63(7):717-728.

9. Kano R, Kimura U, Kakurai M, et al. Trichophyton indotineae sp. nov.: A new highly terbinafine-resistant anthropophilic dermatophyte species. Mycopathologia. 2020;185(6):947-958.

10. Tang C, Kong X, Ahmed SA, et al. Taxonomy of the Trichophyton mentagrophytes/T. interdigitale species complex harboring the highly virulent, multiresistant genotype T. indotineae. Mycopathologia. 2021:1-12.

11. Singh A, Masih A, Khurana A, et al. High terbinafine resistance in Trichophyton interdigitale isolates in Delhi, India harbouring mutations in the squalene epoxidase (SQLE) gene. Mycoses. 2018;61(7):477-484.

12. Nenoff P, Verma SB, Ebert A, et al. Spread of terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton mentagrophytes Type VIII (India) in Germany-“The Tip of the Iceberg?” J Fungi (Basel). 2020;6(4):207.

13. Iwanaga T, Ushigami T, Anzawa K, Mochizuki T. Pathogenic dermatophytes survive in nail lesions during oral terbinafine treatment for tinea unguium. Mycopathologia. 2017;182(7-8):673-679.

Disclosures

Dr. Hainsworth reports no relevant financial disclosures.