is Clinical Professor

of Dermatology

(Retired), Florida

State University

College of Medicine,

Tallahassee, Florida

George Cohen, MD, with John Jesitus

Identifying skin cancers including melanoma in patients with skin of color (SOC) requires dispelling misconceptions, addressing healthcare disparities, and performing careful examinations.

It is a misconception that skin cancer does not occur in non-Caucasian patients. Being black does not make one immune to skin cancer. But it does make skin cancer less likely. Due to this misconception, African-Americans in particular (as a prototypical example of SOC) are not getting enough full-body skin examinations. And that’s leading to misdiagnoses, missed diagnoses, and greater mortality.

Melanoma

Between 2013 and 2017, melanoma incidence rates among African-Americans held relatively steady at one to 2 per 100,000.1 But due to delayed diagnosis, mortality rates among non-Hispanic blacks in the United States are rising.2 In black patients, melanomas are often acral lentiginous melanomas. If you don’t take the shoes and socks off and look at the feet, you may miss an opportunity to save a life.

Oncologists often ask me to identify primary melanomas in patients with metastatic melanoma. In many cases, it’s a subungual melanoma of the foot. Not all melanomas in SOC are black. Some are hypopigmented, and they may look reddish. If a patient has a red, ulcerated lesion on the toe, you can’t rule out melanoma because it’s not black. Acral lentiginous melanomas may possess the c-KIT mutation, which may affect therapeutic decisions.

As in all populations, approximately one of 20 melanomas occurs in the uveal tract. Ocular melanoma can easily be missed. Just looking at the skin alone is not enough to ensure that the person has been properly screened. All patients should undergo a dilated funduscopic exam, which is typically performed by an ophthalmologist or optometrist. Treatment of skin cancers in African-American patients mirrors that for other races. Guidelines generally recommend surgery (including Mohs surgery) with or without adjuvant therapy, depending on stage, prognosis, and other factors.3-5

Treatment for melanoma has gone through the roof. However, it remains to be seen whether checkpoint inhibitors such as ipilimumab (Yervoy, Bristol Myers Squibb), nivolumab (Opdivo, Bristol Myers Squibb), and pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck), or BRAF inhibitors will prove useful in acral lentiginous melanomas. There is reason to suspect that some acral lentiginous melanomas in black patients may have a genetic component. If so, this knowledge might lead to treatments specifically targeting these melanomas.

Treatment of skin cancers in African-American patients mirrors that for other races. Guidelines generally recommend surgery (including Mohs surgery) with or without adjuvant therapy, depending on stage, prognosis, and other factors.

Basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas

In a typical year, I see 5 or 6 African-American patients with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). These patients usually have a predisposing condition. Because patients with albinism can experience the full range of UV-induced actinic damage, for example, I recommend monitoring these patients frequently. Chronic inflammatory conditions that can predispose African-American patients to developing SCC include lupus erythematosus, burn scars, and immunosuppression.

Conversely, for reasons that remain unknown, patients of color with vitiligo rarely develop SCC, despite often having undergone UV therapy for their vitiligo. Though these patients lack pigment, as people with albinism do, those with vitiligo develop far less actinic damage and skin cancers. This is a promising area for study, to see if the signaling pathways in albinism are different from the signaling pathways in vitiligo. The significantly higher incidence of skin cancers in patients with albinism suggests that it takes more than sun exposure alone to promote skin cancers in vitiligo.

Catching SCC in SOC requires paying attention to anywhere a chronic inflammatory condition occurs. For example, chronic cutaneous lupus can be everywhere—the face, the arms, the legs. Rapid exocytic growth may signal malignant transformation. Outside of Gorlin syndrome, basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is so rare in African-American patients that I encounter perhaps one case yearly. Although BCCs are rare in SOC, any unexplained growth requires biopsy. Additional clues to potential BCC include rapid growth and nonhealing lesions.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL)

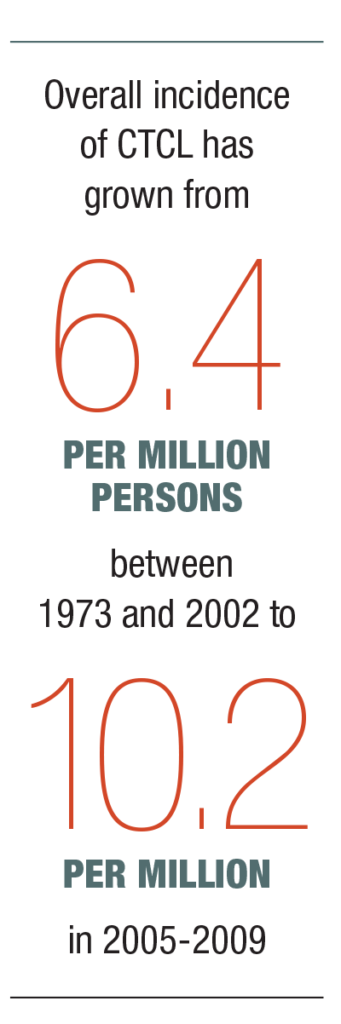

Overall incidence of CTCL has grown from 6.4 per million persons between 1973 and 2002 to 10.2 per million in 2005-2009.6,7 For the latter period, the black-to-white incidence rate ratio was 1.28. Because hypopigmented mycosis fungoides or CTCL often presents as light spots, clinicians can easily mistake it for a fungal infection, eczema, or another benign dermatosis. Often these patients have had these lesions for years, seen multiple doctors, and tried multiple creams and treatments, to no avail.

Photo courtesy of George Cohen, MD.

Patients with hypopigmented CTCL have a good prognosis provided it is caught early. Regard long-standing, widespread hypopigmentation with a high index of suspicion, and send biopsies from at least 2 affected sites for gene rearrangement studies and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Subpopulations of black patients at special risk may include veterans. The United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) compensates Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange who subsequently developed CTCL. Although no studies show conclusively that Agent Orange causes CTCL, the VA has made an administrative decision to compensate these patients because it has observed a significant number of cases among exposed veterans.

Additionally, dermatologists should have a high index of suspicion for skin cancers in patients with HIV who present with unexplained lesions, particularly in the genital area. Fortunately, antiretroviral therapy and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines have greatly reduced incidence of skin cancers in these patients.

On a broader scale, physicians and patients must be mindful of America’s long history of racial disparities in healthcare. As the percentage of Americans who are non-Caucasians grows, it becomes very important to bridge healthcare disparities in all areas, including those in skin cancer detection.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Cohen reports no relevant financial interests.

REFERENCES

- National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER 18). Cancer stat facts: melanoma of the skin. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html. Accessed March 18, 2021.

- Culp MB, Lunsford NB. Melanoma among non-Hispanic black Americans. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16:E79. doi:10.5888/pcd16.180640.

- Swetter SM, Thompson JA, Albertini MR, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. melanoma: cutaneous. Version 2.2021. Published February 19, 2021. Accessed March 18, 2021. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cutaneous_melanoma.pdf.

- Schmults CD, Blitzblau R, Aasi SZ, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. basal cell skin cancer. Version 2.2021. Published February 25, 2021. Accessed March 18, 2021. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nmsc.pdf.

- Schmults CD, Blitzblau R, Aasi SZ, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. squamous cell skin cancer. Version 1.20 21. Published February 5, 2021. Accessed March 18, 2021. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/squamous.pdf.

- Criscione VD, Weinstock MA. Incidence of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the United States, 1973-2002. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(7):854-859.

- Korgavkar K, Xiong M, Weinstock M. Changing incidence trends of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(11):1295-1299.