Counties in Pennsylvania that contained or were near cultivated cropland had significantly higher melanoma rates compared to other regions, according to a new study.

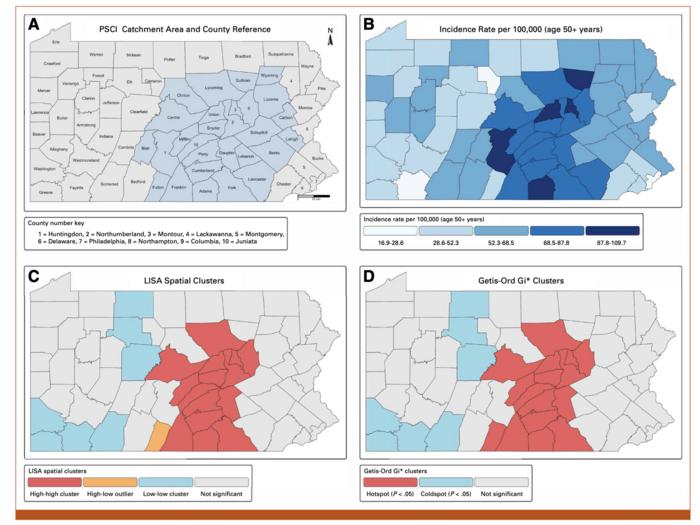

Researchers at Penn State Cancer Institute analyzed five years of cancer registry data (2017 through 2021) and found that adults older than 50 living in a 15-county stretch of South Central Pennsylvania were 57% more likely to develop melanoma than residents elsewhere in the state. The findings appear in the journal JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics.

The cancer cluster includes both rural and metropolitan counties.

“Melanoma is often associated with beaches and sunbathing, but our findings suggest that agricultural environments may also play a role,” says Study author Charlene Lam, MD, MPH, Associate Professor of Dermatology at Penn State Health, in a news release. “And this isn’t just about farmers. Entire communities living near agriculture, people who never set foot in a field, may still be at risk.”

Even after adjusting for ultraviolet radiation in Pennsylvania and socioeconomic factors, two patterns stood out: Counties with more cultivated cropland and those with higher herbicide use had significantly higher melanoma rates, the study showed.

“Pesticides and herbicides are designed to alter biological systems,’ adds Eugene Lengerich, VMD, MS, Emeritus Professor of Public Health Sciences at Penn State and senior author on the paper. “Some of those same mechanisms, like increasing photosensitivity or causing oxidative stress, could theoretically contribute to melanoma development.”

The researchers found that for every 10% increase in the amount of cultivated land, melanoma incidence rose by 14% throughout that region. A similar trend appeared with herbicide-treated acreage: a 9% increase corresponded to a 13% jump in melanoma cases.

Dr. Lam stresses that exposure isn’t limited to the agricultural workers applying the chemicals, as the materials can drift through the air, settle in household dust, and seep into water supplies.

“Our findings suggest that melanoma risk could extend beyond occupational settings to entire communities,” she says. “This is relevant for people living near farmland. You don’t have to be a farmer to face environmental exposure.”

In the paper, the researchers cited other studies that previously linked pesticide and herbicide use with melanoma risk due to the fact that the chemicals have been found to heighten sensitivity to sunlight, disrupt immune function, and damage DNA in non-human animals and plants.

‘Signal, Not a Verdict’

Benjamin Marks, first author on the paper, who is pursuing a medical degree and a Master of Public Health degree at the Penn State College of Medicine, points out that while cropland and increased herbicide use seem to go hand in hand with higher melanoma rates, that doesn’t prove that chemicals commonly used on crops like corn, soybeans, and grains cause cancer, but rather the numbers show a link worth investigating.

He explains that studies like this are valuable for identifying patterns, but can’t necessarily pinpoint individual risk.

“Think of this as a signal, not a verdict,” Marks says. “The data suggest that areas with more cultivated land and herbicide use tend to have higher melanoma rates, but many other factors could be at play, like genetics, behavior, or access to healthcare. Understanding these patterns helps us protect not just farmers, but entire communities living near farmland.”

Dr. Lam’s hope is to better understand the relationship between agricultural practices and public health, as the study’s implications extend beyond Pennsylvania. Similar patterns have been reported in agricultural regions of Utah, Poland, and Italy, the researchers noted in the paper.

She encourages those concerned about their risk to perform regular skin checks and wear sun-protective clothing and sunscreen outdoors. As a next step, Dr. Lam is leading follow-up research in the rural communities within the study area to learn more about practices adopted by farmers and understand where exposure risks could be coming from.

“Cancer prevention can’t happen in isolation,” Lengerich says. “This study demonstrates the importance of a ‘One Health’ approach, an understanding that human health is deeply connected to our environment and agricultural systems. If herbicides and farming practices are contributing to melanoma risk, then solutions must involve not just doctors, but farmers, environmental scientists, policymakers, and communities working together.”