By Cheryl Guttman Krader; Reviewed by Susan J. Bayliss, MD

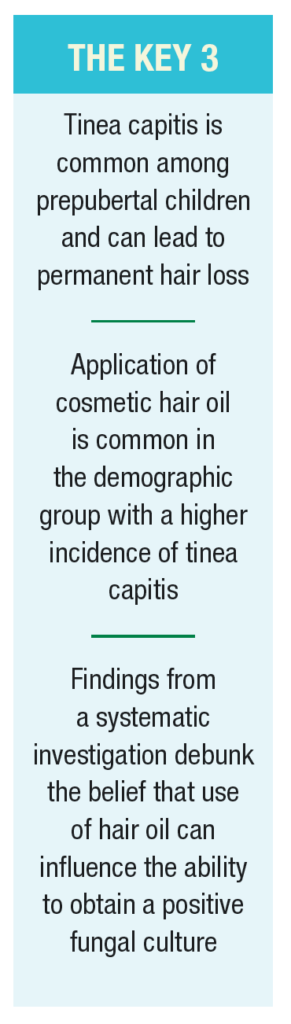

When fungal culture is indicated for diagnosis of suspected tinea capitis, clinicians can feel confident about the reliability of the test results whether the patient’s scalp is dry or oily from the recent use of hair grooming products, according to the results of a recently published study in Pediatric Dermatology.1

Susan J. Bayliss, MD, Professor of Pediatrics and Internal Medicine (Dermatology), Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, is principal investigator of the research that sought to determine whether hair oil affects the sensitivity of fungal cultures for detecting Trichophyton tonsurans in pediatric patients with suspected tinea capitis.

She told The Dermatology Digest that she was taught during her dermatology residency that hair oil can affect fungal culture results. Therefore, patients who were known to be coming to the clinic for signs and symptoms suggesting tinea capitis would be instructed to shampoo their hair and refrain from using any hair grooming products prior to the visit.

“The idea that hair oil can interfere with detection of fungus on culture has been perpetuated over the years and led some dermatology programs to ask patients not to apply hair oil before coming to clinic. However, the origins of the recommendation and the proposed mechanism are unclear. Importantly, there is a lack of evidence to support its veracity,” Dr. Bayliss said.

“As a limitation, our study population was small. However, each patient served as his or her own control, and we feel that based on the results, clinicians should feel free to get a swab for fungal culture whether the scalp is very oily or very dry.”

The study included patients who presented to the pediatric dermatology clinics at St. Louis Children’s Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine with scalp scaling, non-scarring alopecia, positive lymph node swelling, or a high clinical suspicion for tinea capitis. Patients who presented with heavy oil in their hair or whose scalp symptoms could be explained by another disease, such as psoriasis or eczema, were excluded.

All children had specimens collected from the scalp using a cotton-tip applicator before and after 2 drops of cosmetic hair oil were rubbed into the scalp for 5 minutes. The samples were plated on appropriate dermatophyte test media and reviewed for fungal growth for up to 4 weeks.

The study included 28 patients, including 17 male and 11 female. The patients were aged 5.1 ±3.1 years, and 27 (98%) of the 28 children were African American.

The hair oil used in the study was a commercially available product that contained water, coconut oil, propylene glycol, and jojoba oil as its main ingredients. Dr Bayliss said that the hair oil used in the study was selected after canvassing several department employees about the hair grooming products they used. She acknowledged, “It’s possible that the use of some other hair oil products containing different ingredients might affect the sensitivity of fungal cultures.”

Culture results

Of the 28 samples that were collected before hair oil application, 16 (57%) were positive for T. tonsurans. Of the 16 patients with a positive culture, 15 had a positive culture using the sample taken after hair oil application. Of the 12 patients whose culture was negative using the scalp specimen obtained prior to hair oil application, 1 had a positive culture after hair oil application.

Dr. Bayliss noted that because it was involved only a single child, the case in which the culture changed from negative to positive following hair oil application does not raise concern about interference from the hair oil. However, it does underscore a recommendation to repeat the culture if a child diagnosed with another condition is not responding to the recommended treatment.

Testing tips

Understanding best practices for diagnosis of this fungal infection is important considering that it is a common infection in the pediatric population, particularly among prepubertal children, that can lead to permanent hair loss.2

Diagnosis of tinea capitis can be challenging because it may present with subtle findings that can mimic other dermatologic conditions affecting the scalp, such as mild dandruff-like scaling. Therefore, further evaluation beyond physical examination is needed to avoid misdiagnosis.

“It can sometimes be difficult to differentiate between tinea capitis and scalp eczema or seborrheic dermatitis based on the clinical features, and it is also possible that the child has tinea capitis comorbid with another scaling condition,” Dr. Bayliss said.

She noted that fungal culture is the gold standard for diagnosing tinea capitis, and she cited several reasons why she prefers getting a swab specimen for fungal culture rather than performing a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep.

“I do a KOH prep sometimes, but I always do a culture. A downside of the KOH method is that it is more time-consuming for the clinician during what is likely a busy clinic day,” Dr. Bayliss said.

“Although the turnaround time for obtaining the final culture results can be up to 4 weeks, a fungal culture is a more sensitive, reliable, and inexpensive diagnostic tool compared with the KOH prep,” Dr. Bayliss said.

To increase the yield of the culture, Dr. Bayliss recommends moistening the tip of the swab using the culturette transport medium before rubbing it on the scalp.

“This is a quick easy step that can help to increase isolation of the dermatophytes from the scalp and therefore limit false negatives,” she explained.

Because of the delay in obtaining the microbiology report and considering that the oral antifungal agents used to treat tinea capitis in children are generally safe and well-tolerated, Dr. Bayliss said that she will initiate antifungal treatment if she has strong suspicion for diagnosing tinea capitis, such as in a child who presents with posterior lymphadenopathy in addition to scaling on the scalp. However, she waits for the microbiology report in cases in which the diagnosis of tinea capitis is unclear, such as if the child appears to have eczema elsewhere on the body.

A Wood’s lamp examination may also be used for diagnosing tinea capitis. However, it is generally not very fruitful because T. tonsurans does not fluoresce and the test is often misinterpreted in novice hands, Dr. Bayliss said.

References

1. Wichterman CM, Kumar MG, Bayliss SJ. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37(5):977-978.

2. Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Tinea capitis in children: a systematic review of management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(12):2264-2274.

Commentary: Good news about hair oil

By Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD

Tinea capitis continues to pose a significant public health concern worldwide, particularly in young preschool-age children. The most frequently affected US population, African Americans, often use hair oils as a routine hair care practice. This small, prospective, case-controlled study provides reassuring information regarding our ability to obtain reliable cultures in patient populations who utilize hair oils.

This study is a step in the right direction. Nonetheless, it has some shortcomings. The number of patients is small, and patients who had “heavy oil present” initially were excluded. The results tell us about the effect of one application of oil, but not what chronic application of oil does to fungal culture sensitivity. In addition, we cannot state whether the routine use of hair oils poses a risk for acquiring the infection.

Though tinea capitis has been a public health problem throughout history, it has evolved over time. In the US in the 1950s, a Wood’s lamp proved a useful diagnostic tool, as most tinea capitis cases were caused by Microsporum audouinii, which fluoresces, and luckily this Microsporum species was very sensitive to griseofulvin. Fast forward to the latter part of the twentieth century, and Trichophyton tonsurans appears to have made its way from Central/South America to the southwestern US, and Wood’s lamps were no longer useful while griseofulvin proved less and less effective.1

More recently, immigration from African nations to Canada, Europe, and the US has introduced traditionally “African species” to the rest of the world. Species such as T. soudanense and T. violaceum present newer issues, as they are less consistently sensitive to terbinafine, which has supplanted griseofulvin as the treatment of choice in many areas.2 A case of T. mentagrophytes has recently been identified as resistant to terbinafine, adding to concerns regarding evolving dermatophyte resistance patterns.3

One aspect of tinea capitis has not changed, and that is its predilection to preferentially affect people of color. Many theories have been postulated to explain this, including lower socioeconomic status, crowding, and hair-care practices such as tight braiding, straightening, and the use of hair oils. Multiple studies have failed to support any of these as the sole cause. Quality or volume of sebum as important contributors to disease risk have been supported by certain epidemiologic facts. Genetic data on dermatophyte infections and tinea capitis in particular provide support for a polygenic explanation for disease susceptibility for any patient population.4

More data are needed on this topic, but it is nice to know that we can probably depend on our fungal culture results, regardless of the presence of hair oils.

Dr. Fallon Friedlander is Professor Emeritus, Dermatology and Pediatrics, University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, and staff member, Scripps Clinic, San Diego, California.

References

1. Elewski BE. Tinea capitis: a current perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1 Pt 1):1-20;quiz 21-4.

2. Marcoux D, Dang J, Auguste H, et al. Emergence of African species of dermatophytes in tinea capitis: A 17-year experience in a Montreal pediatric hospital. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(3):323-328.

3. Sacheli R, Harag S, Dehavay F, et al. Belgian national survey on tinea capitis: Epidemiological considerations and highlight of terbinafine-resistant T. mentagrophytes with a mutation on SQLE gene. J Fungi (Basel). 2020;6(4):195.

4. Abdel-Rahman SM. Genetic predictors of susceptibility to dermatophytoses. Mycopathologia. 2017;182(1-2):67-76.