Dermatologic toxicities resulting from cancer treatments are common and debilitating and can significantly impair a patient’s quality of life, potentially requiring dose adjustments or discontinuation of treatment that can compromise outcomes.

These concerns have sired a new and growing dermatology sub-specialty known as supportive oncodermatology, which encompasses the diagnosis, treatment, and management of skin, hair, and nail conditions caused by cancer treatments.

Supportive oncodermatology’s lofty and overarching goals? Keep patients on their life-saving cancer therapies and improve their overall quality of life.

- What’s Driving the Growth of Supportive Oncodermatology?

- Delineating the Cutaneous Adverse Effects of Cancer Treatments

- Mitigation Strategies: To Dose Reduce or Not To Dose Reduce?

- When to Call In a Supportive Oncodermatologist

- Inside the Oncodermatology Toolbox

- Preserving and Improving Quality of Life for Cancer Patients

- Prevention of Dermal Toxicities During Cancer Treatment

- Future Directions in Oncodermatology

What’s Driving the Growth of Supportive Oncodermatology?

The evolution of oncodermatology has been driven by the emergence of new cancer treatments, including immunotherapy agents including checkpoint inhibitors like PD-1 inhibitors and targeted therapies such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) inhibitors, says Brittany Dulmage, MD, an Oncodermatologist at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, OH.

“As new cancer treatment types have emerged, they have carried with them different hair, skin, and nail side effects that have kind of necessitated experts to manage those so that patients can stay on their life-saving cancer therapy, but still maintain a good quality of life,” she says.

Immunotherapy, in particular, has really cemented the development of oncodermatology as a field, she says.

“The number of cancers that can be managed with immunotherapy and the types of immunotherapy that are available has just exploded,” she says. “There are a lot of rashes that are associated with immunotherapy, from pretty mild things that happen early in treatment to very robust reactions that would require hospitalization to more delayed development of dermatologic conditions that can even happen after someone’s been on therapy for a year or more,” says Dr. Dulmage.

The field has changed rapidly over the last 20 years because of huge advances in cancer therapeutics, agrees Meghan Heberton, MD, Director of Oncodermatology at Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center of UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, TX. “The breadth of potential cutaneous effects from novel targeted agents and immunotherapy has significantly expanded the demand for dermatologic expertise,” she says.

Just 15 years ago, there was only one oncodermatologist: Mario Lacouture, MD. Now, the Chief of the Dermatology Division at the NYU Grossman Long Island School of Medicine and Medical Director of the Symptom Management Program at the Perlmutter Cancer Center of the NYU Langone Hospital – Long Island in Mineola, NY, Dr. Lacouture started the first program focused on skin, hair, and nail conditions in cancer patients and survivors in 2006 at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, NY.

Now, most major cancer centers have supportive oncodermatology programs and societies such as the Oncodermatology Society and the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV)’s European Task Force of Dermatology for Cancer Patients, which exist to help propel the specialty and develop standards of care for dermal toxicities associated with cancer treatments. More and more academic departments are creating oncodermatology programs and recruiting dermatologists specifically to interface with their cancer centers, says Ian W. Tattersall, MD, PhD, Director of Oncodermatology at NYU Langone Manhattan and an Assistant Professor of Dermatology at NYU Grossman School of Medicine in New York, NY.

There are other corresponding factors that are also responsible for the growth of this subspecialty, adds Jesse Hirner, MD, MS, Director of Supportive Oncodermatology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) and a Dermatologist at Nebraska Medicine in Omaha, NE. “Cancer diagnoses are rising sharply, especially among baby boomers, and there is a dearth of medical oncologists,” he says. “Supportive specialists in dermatology and other fields are now doing what they can to support medical oncologists.”

Unfortunately, not enough residents are trained in supportive oncodermatology to keep pace with this growth …yet. In a survey of 442 dermatology residents from 20 countries, participants reported receiving less comprehensive training in supportive oncodermatology. Only 41% received complete training compared to immunodermatology (75%), cutaneous oncology (75%), dermoscopy (64%), and dermatologic surgery (50%), the study showed.1 Only 17% of the residents reported feeling confident in managing the dermatological toxicities associated with anticancer treatments.

There just aren’t enough dermatologists who specialize in this field, says Dr. Heberton. General dermatologists will see patients with toxicity from cancer treatment.

“I think it is so helpful when a dermatologist in the community can now connect that the patient’s pembrolizumab (Keytruda, Merck) may be the reason for the new-onset psoriasis, and closing that loop is very valuable,” she says.

“It’s a good idea to be comfortable with some of the more common skin toxicities, and to know what treatments to avoid if possible, but most important is to practice dermatosis-directed therapy: treat the toxicity like the primary dermatosis it resembles, and you’re generally off to a great start,” Dr. Tattersall says.

|

|

Delineating the Cutaneous Adverse Effects of Cancer Treatments

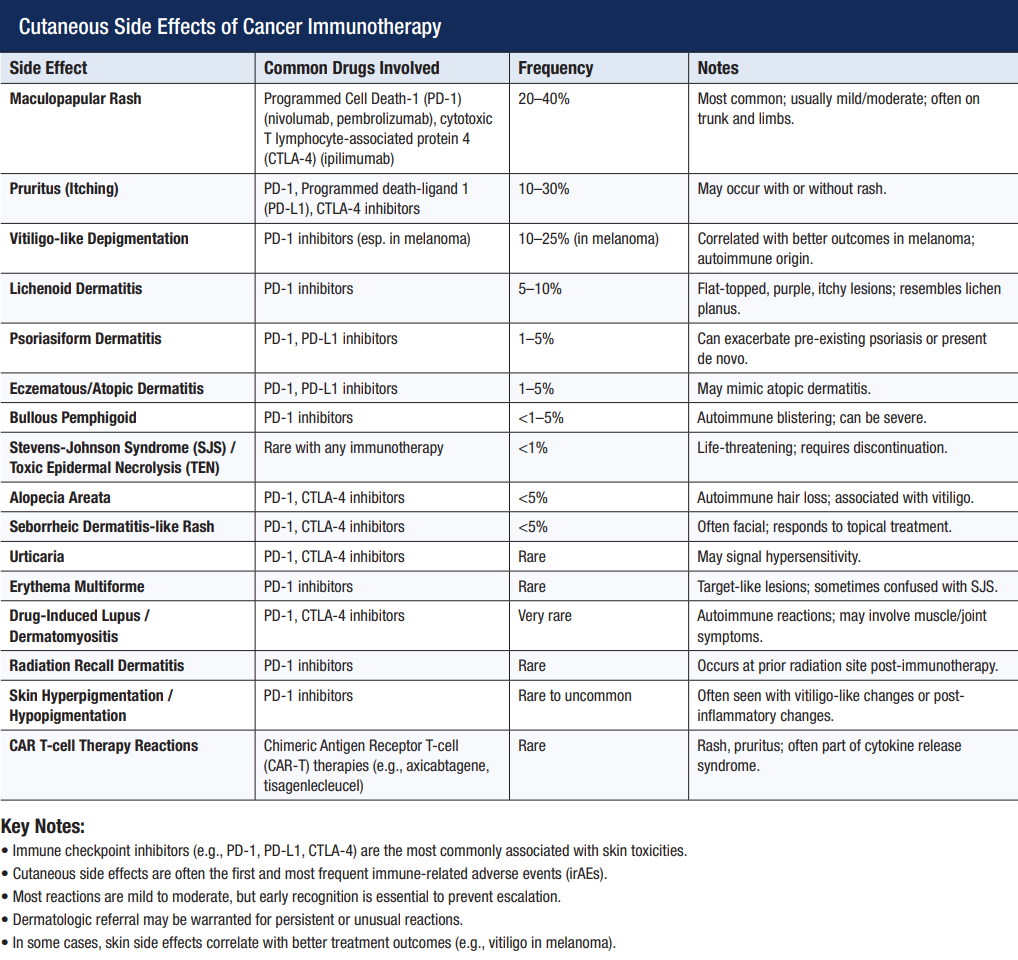

Radiation can cause burns, and chemotherapy is known to cause hair loss and onycholysis, but Dr. Heberton mostly sees patients with skin side effects from immunotherapy and targeted therapies. “Immunotherapies have very unpredictable side effects because of their mechanism of action,” she says. Both the time of onset and diagnosis are hard to predict.

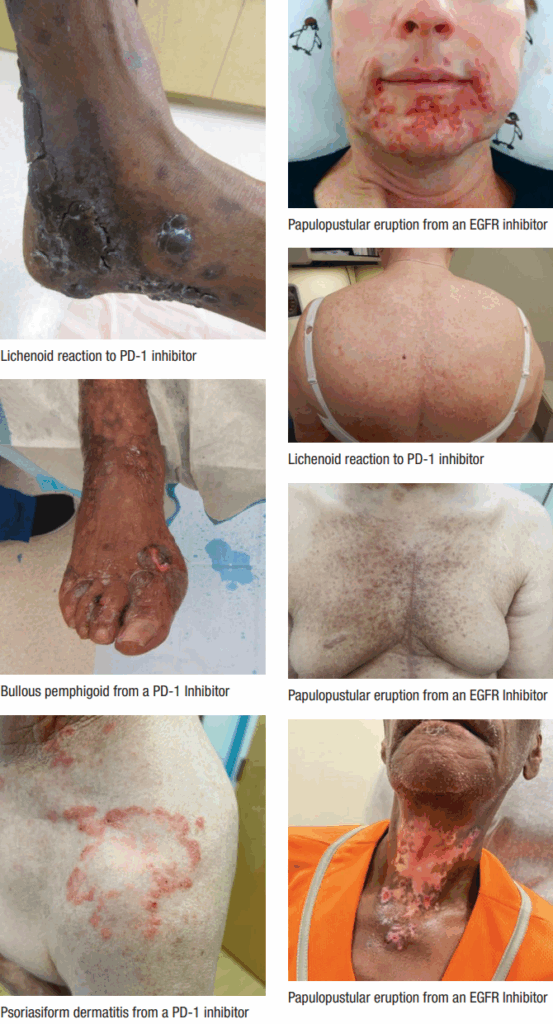

“This class of therapies disinhibits T cells, and therefore, immune-related adverse events are possible in multiple organs, especially the skin,” Dr. Heberton explains. “We see a range of conditions such as

psoriasis, lichenoid dermatitis, and even rare dermatologic diagnoses like generalized morphea from these therapies.”

With immunotherapy, side effects can be durable and last even when immunotherapy has stopped. “It is possible to have morbid adverse events, too, that demand urgent treatment such as cutaneous infections, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).”

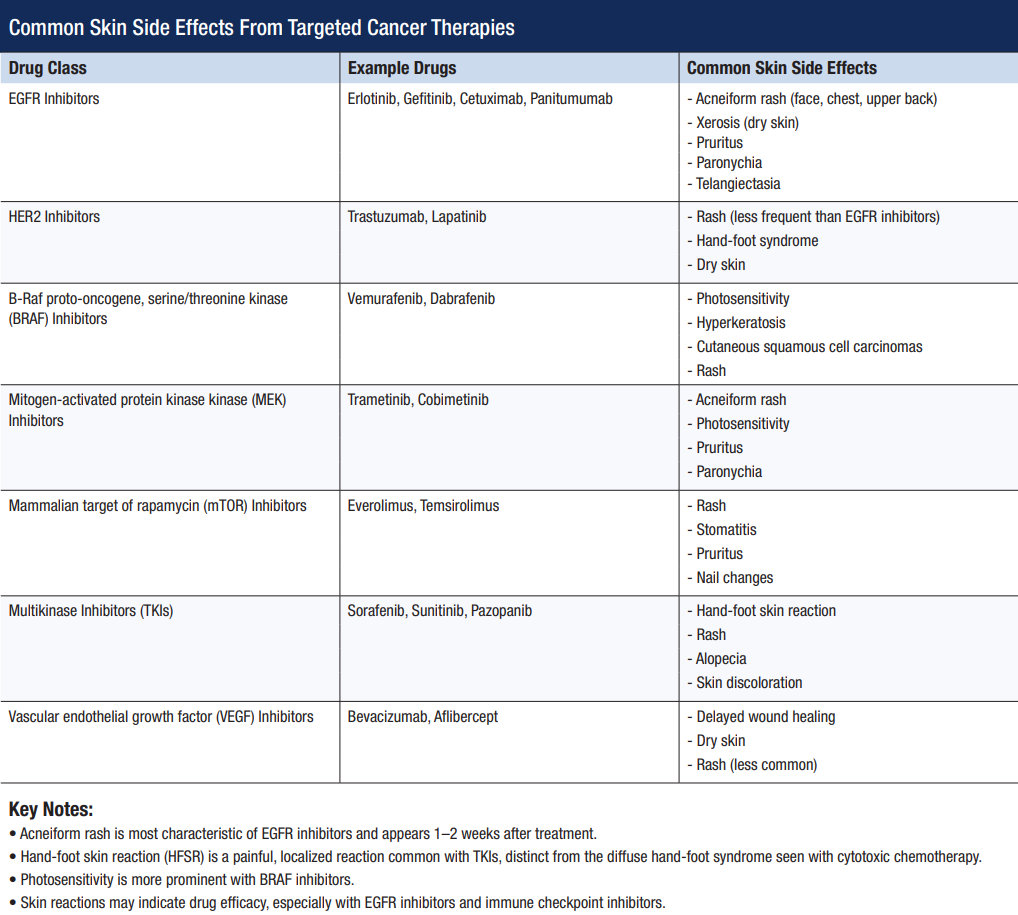

There are many targeted cancer therapies available today, but one that commonly causes cutaneous side effects is EGFR inhibitors. These drugs are linked to the development of acneiform eruptions, eczematous dermatitis, predisposition to staphylococcal infections, and other skin changes, she says.

Combinations of cancer therapies can also cause cutaneous reactions, says Dr. Tattersall. “We’re also increasingly seeing these families of therapy used in combination with one another, so there are many situations where it falls to the oncodermatologist to tease apart the different therapies and determine which one is causing each aspect of a patient’s dermatologic disease.

Mitigation Strategies: To Dose Reduce or Not To Dose Reduce?

One of the main tenets of supportive oncodermatology is to make sure patients can stay on their treatments and maintain dose intensity.

“Dose intensity is very important and is associated with survival for certain drug-cancer combinations,” says Dr. Hirner. “It may be reduced due to cutaneous side effects.”

Dose reduction is possible if a patient has side effects from cytotoxic or targeted therapy.

“If the patient is on immunotherapy, then that is not a possible strategy, and therapy will either be held briefly with rechallenge later or permanently held,” Dr. Heberton says.

“Differences in dosing intervals, such as every three or six weeks, may help mitigate some of the immunotherapy side effects,” Dr. Dulmage says. “I may advocate that a treatment is delayed slightly while we try to get a cutaneous reaction under control.”

“Dose reduction is not ideal since our goal is to keep patients on their optimal oncologic therapy,” Dr. Tattersall says. “There are absolutely some instances where the only way to bring skin toxicity back down to a tolerable grade is to dose pause or dose reduce.”

All photos courtesy of Adam Friedman, MD

When to Call In a Supportive Oncodermatologist

Oncodermatologists can effectively manage certain skin reactions to cancer treatment. “A great example is the acneiform eruption, which happens with EGFR inhibitors,” Dr. Dulmage says.

“When EGFR inhibitors first were utilized, patients were referred much more frequently to dermatology for that eruption, but now oncologists know it’s going to happen, and they’ve got a toolbox of things they can use to treat it.”

“I only see patients who don’t respond to first- or second-line therapy for EGFR inhibitor-related acneiform eruptions, where we need to get a little bit more creative or more sophisticated with how we’re trying to manage the eruption,” Dr. Dulmage says.

“We tend to get more involved when there’s a brand-new oncology treatment where there’s a skin side effect that’s a bit more unknown,” she adds.

Many clinical trials of novel cancer therapies are underway that may cause cutaneous reactions. “We don’t know what’s going to happen in the skin, so we get involved earlier to help characterize that reaction, categorize it, and come up with a plan,” she says.

“The broader world of oncology is also increasingly recognizing the importance of skin to cancer therapy, and dermatologists are becoming involved not just in the treatment of patients, but also in advising pharmaceutical companies during drug development, to interpret and triage the skin toxicity of their new drugs and develop protocols for managing them,” says Dr. Tattersall.

“Most patients will only see an oncodermatologist when problems arise, but we do occasionally see people in a prophylactic setting when they are contemplating a high-toxicity drug or have a medical history that makes them more likely to have skin issues,” Dr. Tattersall says.

There is also a role for oncodermatologists after cancer treatment has ended. “Patients oftentimes are interested in trying to recover hair growth as much as possible or to get their nails back to normal as quickly as possible, and so they’ll often ask for referrals to an oncodermatologist or dermatologist to facilitate that,” Dr. Dulmage says.

Inside the Oncodermatology Toolbox

There are many interventions in the oncodermatology toolbox, experts tell TDD.

“We are getting increasing data that show some of the drugs used in dermatology, such as dupilimab (Dupixent, Sanofi & Regeneron), are safe to use in this population without increasing risk for cancer recurrence or decreasing survival,” Dr. Hirner says.

Dupilumab can improve itch, rash, redness, and scaliness. “For immunotherapy-induced BP, dupilumab can reduce blistering and mucosal findings, making it easier for the patient to eat and drink,” he says.

“Dermatologists may jump to powerful immunosuppressants such as systemic corticosteroids, cyclosporine, or mycophenolate, but we have safer options that don’t impact oncology outcomes as much,” he adds. These may include dupilumab, rituximab, or IVIg (intravenous immunoglobulin).

Systemic steroids should be avoided in immunotherapy recipients when possible. “They worsen survival among immunotherapy recipients and make cancer recurrence more likely,” Dr. Hirner says.

Dr. Dulmage agrees. “Steroid-sparing is huge, and in order to do steroid-sparing, it’s important that we classify their reaction,” she says.

If a patient on immunotherapy develops red, scaly, itchy rashes, making a differential diagnosis can be tricky. “It could be eczema, it could be psoriasis or a lichenoid drug reaction, and each one of those things has a better and pretty specific treatment approach.”

To make the call, oncodermatologists will conduct a thorough skin exam and order a biopsy to diagnose the rash, pick a more sophisticated treatment, and avoid steroids, Dr. Dulmage adds.

Preserving and Improving Quality of Life for Cancer Patients

Mitigating cutaneous toxicity makes cancer treatment more tolerable, both physically and psychologically, Dr. Tattersall says. “That means our patients are more likely to stay on their optimal treatment course and will have a better quality of life while on those treatments, many of which are lifelong.”

Some toxicities and hypersensitivity reactions can cause emergent threats to patients’ health, and many more serve as a constant daily, visual, and public reminder of the patient’s disease, he adds.

Enrollment in a supportive oncodermatology program is associated with a significantly improved quality of life score, according to a survey from the George Washington University (GW) Cancer Center published in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.2

To identify the impact of these programs, the group at GW performed a crosssectional survey of adult cancer patients enrolled at the Supportive Oncodermatology Clinic at GW Cancer Center. Those who met the inclusion criteria were invited to complete an online survey with questions adapted from the Dermatology Life Quality Index and Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire. The respondents reported satisfaction with the care they received at the GW Supportive Oncodermatology Clinic, especially regarding providers’ interpersonal manner and communication. They would recommend this type of care to other cancer patients.

Before receiving care at the clinic, patients had an average quality of life score of 6.5, indicating a “moderate effect” that dermatologic adverse events have on quality of life. On average, scores were significantly reduced by 2.7 points after joining the clinic.

Prevention of Dermal Toxicities During Cancer Treatment

Prevention may also help stave off cutaneous reactions among patients undergoing cancer treatment.

Being forewarned is being forearmed when it comes to acneiform rash associated with EGFR inhibitors, says Dr. Hirner. “We can prevent by starting the patient on topical steroids and oral antibiotics on Day One,” he says.

Being gentle with the skin and avoiding harsher topical medications can also keep cutaneous reactions to cancer therapy at bay, Dr. Dulmage says. “Just focusing on good moisturization and inspecting their skin to see if things are changing and bringing it to the doctor’s attention is helpful.”

Hand-foot syndrome (HFS), also known as palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, is a common side effect of certain chemotherapy and targeted therapy drugs.

“It is characterized by redness, swelling, peeling of the palms and the soles, and quite common with the oral medicine capecitabine,” says Dr. Dulmage. “You can apply a topical gel to the hands and the feet to reduce the risk of that happening,” she says.

“When patients are going on chemotherapy, they can actually cool certain regions of the skin with a machine, cool pack, or cap to reduce delivery of the chemotherapy to those areas and prevent hair loss or skin and nail changes,” she says. Cold therapy should be started at the very first infusion of chemotherapy, she says.

Dr. Heberton agrees that good skin care, judicious use of sunscreen, and moisturizing are essential to stave off cutaneous reactions to cancer therapy. “If a patient has a pre-existing dermatologic condition like psoriasis or lichen planus prior to starting immunotherapy, then there should be a strategy for management prior to starting immunotherapy.”

Dr. Tattersall adds, “Many toxicities are also pressure, friction, and trauma-sensitive, so avoiding high-impact activities or exercise, using gloves when doing wet work, and wearing shoes with loose toe caps and supportive insoles can do a lot to mitigate certain types of skin toxicity,” he says.

Future Directions in Oncodermatology

Currently, the drug development pipeline is filled with therapies that may address cutaneous side effects of cancer therapies. Hoth Therapeutics is developing HT-001, a topical gel to treat EGFR inhibitor-related skin toxicities. HT-001 is a proprietary, non-steroidal topical formulation that aims to alleviate itching and irritation without the systemic side effects of traditional treatments.

“There are studies looking at the use of a topical agent to vasoconstrict blood vessels on the scalp so that chemotherapy doesn’t get delivered there,” Dr. Dulmage says. Other interventions involve using pressure on the scalp, hands, or feet to reduce delivery of medication to this area,” she says.

And this is just the beginning.

Skin toxicity is increasingly recognized as a critical element of oncology, both from a clinical and from a pharmaceutical perspective, Dr. Tattersall says.

“Expect to see more oncodermatology departments and more oncodermatologists in academic practice, and expect to see more granular and accurate descriptions of the toxicity profiles of new cancer drugs,” he says.

Historically, there have not been any products specifically designed, or U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved, to treat cancer treatment toxicities; times are changing, he says. “There are already a number of

drugs in clinical trials specifically for cancer treatment toxicity mitigation, so expect to see those emerging into the marketplace in the next few years,” he says. “We’re hopefully heading towards an era where the importance of skin toxicity is increasingly included as part of a cancer patient’s multidisciplinary care, and with that will come new tools to work with, new pathways of triage and treatment, and new dermatologic opportunities to better allow cancer patients to live happier and healthier lives.”

REFERENCES

- Ortiz-Brugués A, Fattore D, Boileau M, et al. International survey on training of dermatology residents in supportive oncodermatology: the RESCUE study. Support Care Cancer. 2025;33(5):412. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00520-025-09459-w

- Aizman L, Nelson K, Sparks AD, Friedman AJ. The influence of supportive oncodermatology interventions on patient quality of life: A cross-sectional survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(5):477–482. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32484625/