Interleukin-38 (IL-38) may drive the mechanisms underlying skin renewal, finds a study in Cell Reports.

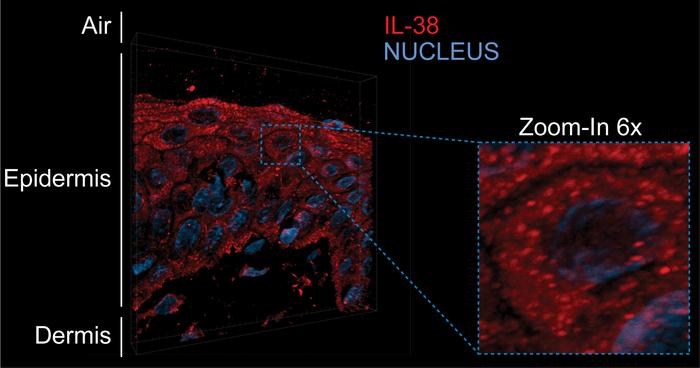

A team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) has observed IL-38 for the first time in the form of condensates in keratinocytes. The presence of IL-38 in these aggregates is enhanced close to the skin’s surface exposed to atmospheric oxygen. This process could be linked to the initiation of programmed keratinocyte death.

The epidermis protects the body from external aggression. Renewal of the epidermis relies on stem cells located in its lowest layer, which constantly produce new keratinocytes. These new cells are then pushed to the surface, differentiating along the way and accumulating protein condensates. Once they reach the top of the epidermis, they undergo cornification to create a protective barrier of dead cells.

“The way in which the epidermis constantly renews itself is well documented. However, the mechanisms that drive this process are still not fully understood,” explains study author Gaby Palmer-Lourenço, Associate Professor at the Faculty of Medicine of UNIGE.

IL-38 is known for its role in regulating inflammatory responses, and its presence in keratinocytes was previously associated with the preservation of the skin’s immune balance. “In keratinocytes in vivo, we found that IL-38 forms condensates, specialized protein aggregates with specific biochemical functions, a behavior that was not known for this protein,” says Palmer-Lourenço.

Even more curious, the closer the keratinocytes were to the surface of the skin, the greater the amount of IL-38 within these condensates.

Blood vessels stop in the skin layer located below the epidermis. Therefore, the quantity of oxygen available for the keratinocytes is lower in the basal layers of the epidermis compared to the top layers that are directly exposed to the air that surrounds us. However, even though it is necessary to maintain cell functions, oxygen also causes oxidative stress by forming free radicals. “We were able to show that oxidative stress does indeed cause IL-38 condensation under laboratory conditions,” confirms study author Alejandro Díaz-Barreiro, Postdoctoral Fellow at the UNIGE Faculty of Medicine.

“Our results lead us to believe that, as we move closer to the epidermal surface, the increasing oxygen concentration promotes the formation of protein condensates, indicating to keratinocytes that they are in the right place to enter cell death,” adds Gaby Palmer-Lourenço.This hypothesis provides new leads to decipher the mechanisms of epidermal renewal. It could also pave the way for a better understanding of the pathological mechanisms underlying certain skin diseases, such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis. These questions will be further examined by the research group in future studies.

Díaz-Barreiro is already working on the next step: “In the model we used previously, the effects of oxidative stress were artificially induced in a single layer of keratinocytes, a scenario that differs from the actual situation in the skin. We are therefore developing a new experimental system to apply oxygen gradients to in vitro reconstituted human epidermis. In this model, only the skin surface will be exposed to ambient air, while the other layers will be protected. This will allow us to study in detail the effect of oxidative stress on epidermal renewal.”

By enabling a more precise analysis of human cells, this new system will provide an alternative to animal models often used for the study of skin biology and disease.

PHOTO CAPTION: IL-38 forms condensates in human epidermis. Immunostaining of the IL-38 protein (red) in human epidermis from a healthy donor revealed granular structures that are more intense in the layer of living keratinocytes that is most exposed to air. Nuclei are stained in blue.

CREDIT: © ALEJANDRO DIAZ-BARREIRO