With Candrice R. Heath, MD, FAAP, FAAD

Dermatologists practicing in all types of settings have a high probability of seeing children and adolescents with skin of color (SOC) considering the group represents a growing majority of the U.S. pediatric population. Providing effective care for these patients requires the knowledge that some dermatoses present in unique ways in SOC. Success also depends on skillful interactions incorporating awareness of ethnic, racial, and cultural issues that impact perceptions of the clinical encounter and the likelihood of treatment adherence, according to Candrice R. Heath, MD.

Dr. Heath, who is an assistant professor of dermatology at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine, Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, discussed pediatric dermatoses in children with SOC at the Mark Allen Everett, MD, Skin of Color Symposium, which was held in April 2021 by the Department of Dermatology, University of Oklahoma College of Medicine. In the presentation, she noted that when parents/guardians with SOC take their children for a dermatologic visit they might also be bringing angst from the psychosocial sequelae of their own skin concerns, as well as from past negative interactions with dermatologists. When dermatologists do not incorporate this insight into their communication, examination, and treatment recommendations, they risk patient dissatisfaction and increase the probability of an unfavorable clinical outcome.

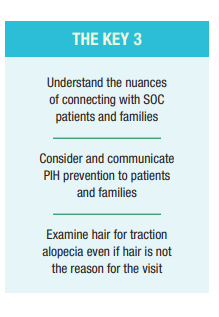

“It is not just knowledge of the science behind making an accurate diagnosis and selecting an appropriate treatment that matters. Making a connection with the patient and family through the art of effective communication is another important piece,” Dr. Heath emphasized.

Case study: atopic dermatitis

Dr. Heath illustrated her points with a discussion of atopic dermatitis (AD), a condition that is more prevalent in certain racial/ethnic groups compared to non-Hispanic whites, and which tends to be particularly severe in Black children.

Knowledge of differences in presentation facilitates the effective diagnosis of AD in patients with SOC. For instance, AD in individuals with darker skin tones is more likely to appear with papular or follicular lesions and hyperpigmented lichenified plaques accompanied by darkening or a violaceous hue of the skin rather than with erythematous plaques.

For added accuracy in identifying an AD flare, Dr. Heath recommended relying on palpation as well as visualization. “Close your eyes and use your fingertips to feel for follicular prominence,” she explained.

A greater risk for developing postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) is also a key feature of AD in patients with SOC, and the same is true for acne, another common dermatosis in pediatric patients with SOC. Dermatologists should know that these “dark spots” or “stains” (“manchas” in Spanish) may be what most distresses the patient or parent accompanying the child.

“It is important to state that you see the dark spots and affirm that the treatment plan is designed to help with the cause of the pigment change. Controlling the primary disease will limit the future development of PIH, and for acne in particular, some of our therapies, such as topical retinoids and azelaic acid, have an additional advantage of simultaneously improving the PIH,” Dr. Heath said. “If this information is not communicated during the visit, parents are likely to leave dissatisfied, thinking that the appointment was a waste of time and the doctor does not know what he or she was talking about.”

Hypopigmentation or depigmenting disorders are other leading concerns in SOC patients. When treating such disorders, knowledge of and sensitivity to the cultural beliefs and traditions as they pertain to different SOC groups are critical considerations. For example, adults of Indian descent may fear that if the condition persists, it will negatively impact their child’s future marriage prospects.

“Don’t discount a small patch of vitiligo in a young child as a minor cosmetic issue because the parent may be worrying about its later life impact,” Dr. Heath cautioned.

Hair and scalp disorders

Practicing cultural sensitivity is also crucial when performing the diagnostic examination and recommending treatment for hair and scalp disorders in SOC patients. In particular, dermatologists need to appreciate the unique aspects of haircare practices and hair texture among patients with tightly coiled hair. It is worth noting that styling a child’s hair, particularly for Black children, is a time-intensive process that also often provides an important bonding experience.

Another consideration is that the hair of Black individuals can be quite dry and prone to breakage. Consequently, some dermatologists may feel apprehensive and uncomfortable about examining the hair and scalp in Black patients; they may feel they lack the skill set or perceive that the patient or caregiver might prefer that the hair not be touched. Avoiding physical contact, however, can result in dissatisfaction with the encounter and may be interpreted as a sign of racial insensitivity.

“The key to a winning interaction is to ask if it is okay to examine the hair and ask specific questions about hair care practices that display knowledge in this area,” Dr. Heath said. She also advised against combing the hair to facilitate the exam as this can lead to hair breakage and patient discomfort. Instead, Dr. Heath recommended that dermatologists ask the patient or parent to remove any hair accessories, such as ties or barrettes, rather than doing it themselves.

Whether or not a hair or scalp disorder is the reason for the visit, dermatologists should look for signs of traction alopecia in Black children with tight ponytails or braids. Decreased hair density of the frontal hairline, referred to as “thinning edges” by adult Black women, may be less noticeable in young children when hair loss is limited. Fortunately, at this early stage hair loss from traction alopecia is reversible, and the earlier it is addressed, the better the long-term outcome is likely to be.

“Ask about pain as a sign that the hairstyle is too tight and try to intervene by explaining that switching to a low-tension hairstyle can avoid the risk of scarring with devastating permanent hair loss,” said Dr. Heath.

“Again, the approach to communicating the message is key,” Dr. Heath continued. “While physicians may think they should not raise the matter if the patient or parent has not expressed that hair loss is a problem, there are ways to initiate the conversation and offer professional advice so that it is accepted.”

Tips for treatment selection

When prescribing a retinoid for acne treatment to SOC patients, dermatologists should keep in mind that PIH is a primary concern of such patients, and consequently be sure to include strategies that will minimize the risk of retinoid dermatitis, which can also cause PIH, as part of their prescription counseling.

Since sun protection is another important factor in PIH management, patients should also be educated about sunscreen application.

“Thinking it is not needed, many people with SOC have never used sunscreen. To encourage sunscreen use, suggest products that will not leave a white residue on the skin,” Dr. Heath said.

When prescribing treatment for seborrheic dermatitis in a Black patient, dermatologists should consider that antifungal shampoos could worsen hair dryness and promote breakage. To minimize these problems, patients should be told to apply the product to the scalp only.

Taking into account hair styling practices, certain vehicles may be preferred when prescribing a topical steroid for a scalp disorder. For example, if a patient with tightly coiled hair is using heat alone to straighten the hair, applying medication in a solution will cause the hair to revert to its natural state, Dr. Heath noted.

“Describe the available vehicle formulations with potential pros and cons, and ask if the patient or parent has a preference,” Dr. Heath advised. “Not only will this help with gaining patient satisfaction and cooperation with the treatment, but it can also be an opportunity to gain new insights into cultural practices that will help with tailoring care in the future.”

by Cheryl Guttman Krader