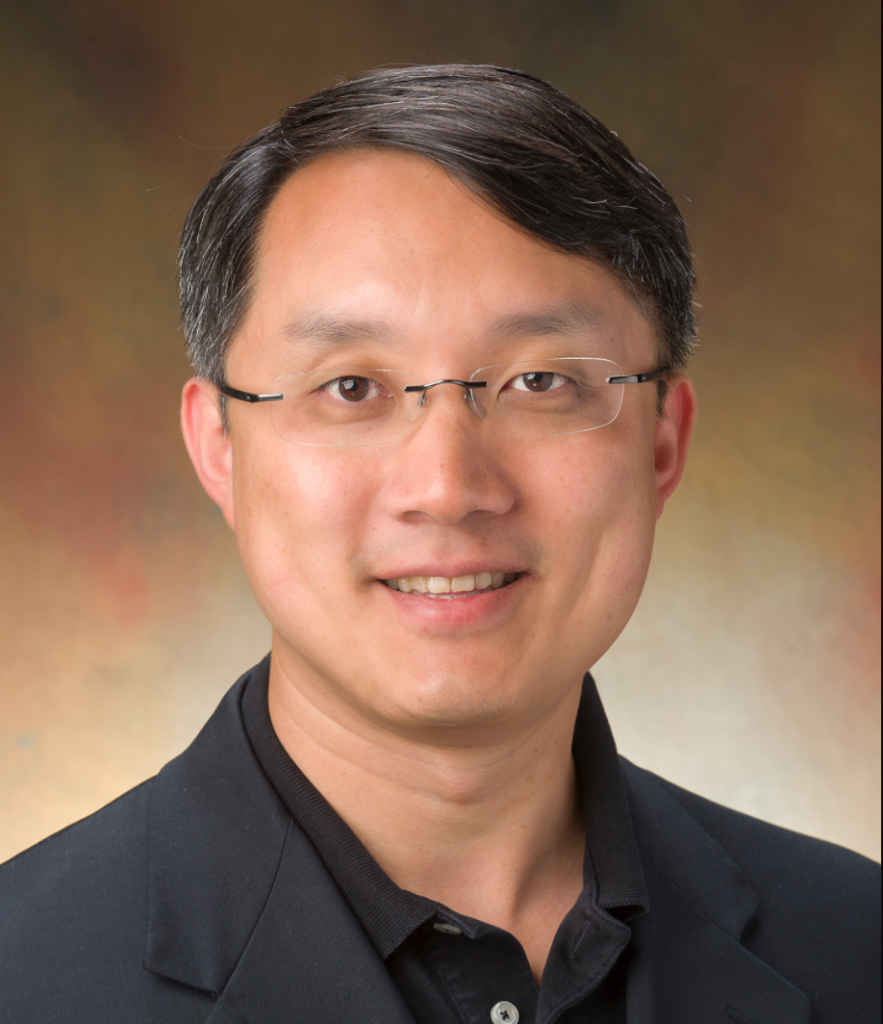

Albert C. Yan, MD Professor of Pediatrics and Dermatology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Albert C. Yan, MD, with Cheryl Guttman Krader

CASE HISTORY

A 3-week-old boy was seen for evaluation of a congenital segmental vascular birthmark involving the right lower leg (Figure 1). The parents were told in the delivery room that the birthmark was a faint port wine stain (capillary malformation), but the parents noted that the lesion had darkened since birth.

The birthmark was initially suspected to be a reticulated port wine stain, but as follow-up continued, the plaques became thicker, scaly, and hyperkeratotic. The child began to walk at about 12 months of age, and the parents noticed that he was experiencing discomfort and exhibited pinpoint bleeding (Figure 2).

What is your suspected diagnosis?

AN EVOLVING VASCULAR BIRTHMARK WITH INTERMITTENT BLEEDING AND PAIN

DISCUSSION

Vascular anomalies that either are present at birth or appear early in infancy should initially be followed more frequently for possible changes. Segmental lesions may evolve into segmental hemangiomas or represent angiokeratoma circumscriptum (AC) or verrucous hemangioma (VH). In this case, the history of enlargement with development of pinpoint bleeding confirmed the clinical suspicion that the lesion was not a port wine stain but rather in the AC/VH spectrum.

Angiokeratoma circumscriptum and VH are rare vascular anomalies that may be congenital or may develop within the first few months of life.1,2 These entities typically present unilaterally as violaceous hyperkeratotic plaques on

the lower limbs.1,2 They are distinguished by vascular alteration depth.1,2 Angiokeratoma circumscriptum is a more superficial anomaly, with vascular alterations limited to the papillary dermis, whereas in VH the vessels reach into the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue.1,2 On immunohistochemistry, VH will frequently stain positive for Wilms tumor 1 protein (WT1) and glucose transporter-1 protein (GLUT1), whereas there are no reports of AC showing positivity for these markers.1,3

Both AC and VH expand in size with time and become thicker, keratotic, and verrucous. As in this child’s case, these lesions often bleed and can become painful. The progressive course of AC/VH contrasts with the pattern of proliferation-plateau-involution followed by infantile hemangiomas. If there is any doubt about the diagnosis, a small biopsy sample can be taken to look for the characteristic histopathologic features and immunohistochemical markers for VH.

Limited therapeutic options exist for AC/VH. Excision may be done to remove smaller plaques and may be curative, but there is a tendency for recurrence if the entire lesion is not removed, which can particularly occur with VH given the depth of involvement.2

If excision is being considered, a biopsy to differentiate between AC and VH may be done to prognosticate the likelihood of recurrence. If excision is not feasible because of lesional extent, surgery may still be considered for

selected areas that are painful or prone to bleeding.

Various lasers have been used as a less disfiguring treatment approach for AC/VH, but the results have been variable.4-6 Pulsed dye laser (PDL) used as monotherapy is not very effective, although limited improvement can

be seen when early treatment is initiated. Some investigators have had success with alternative modalities, including the combination of PDL with the Nd:YAG laser or selected surgical removal, which have provided more efficacy for improving lesion appearance and providing symptomatic relief. Reports of reasonably good responses achieved with this dual laser approach generally involved a dozen or more treatment sessions. Topical sirolimus compounded with different concentrations of the active ingredient has also been used to treat AC/VH, but with variable benefit.7,8

CASE CONTINUED

In a discussion of treatment options for this child, the family was informed about the challenges of undertaking surgery given the extent of the lesions and location. They were informed that cosmetic and symptomatic improvement might be achievable using a more conservative approach with laser and topical treatment but

would be a long and slow process.

When the child was 14 months old, treatment was initiated with topical sirolimus cream, 1% that resulted in reduction of the hyperkeratosis within 3 months.

Laser treatment with a PDL was initiated at age 19 months using a fluence of 8 J/cm2 and escalated at each subsequent visit as tolerated. The PDL was selected because we did not have access to an Nd:YAG laser. The laser treatments were done under local anesthesia using topical EMLA cream and repeated every 2 months, with significant benefit noted over time while continuing topical sirolimus.

Topical sirolimus is not currently commercially available and must be compounded. Because of the ongoing course of treatment with sirolimus, safety monitoring was done with periodic laboratory assays, including complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, and sirolimus blood level. The child developed a transient episode of leukopenia attributed to viral suppression but counts recovered promptly and have not recurred despite continued therapy. Otherwise the treatment was well-tolerated.

At the last available visit, the child was 51 months old and had been on topical sirolimus for 3 years and undergone 14 PDL sessions (Figure 3).

Complete clearing was achieved for several of the smaller, more superficial areas of the lesion, and the larger, thicker plaques had become thinner and significantly regressed. The lesion was no longer bleeding, even if exposed to minor trauma. The parents wanted to continue treatment as they were optimistic about achieving continued improvement.

REFERENCES

- Oppermann K, Boff AL, Bonamigo RR. Verrucous hemangioma and histopathological differential diagnosis with angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(5):712-715.

- Clairwood MQ, Bruckner AL, Dadras SS. Verrucous hemangioma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38(9):740-746.

- Trindade F, Torrelo A, Requena L, et al. An immunohistochemical study of verrucous hemangiomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40(5):472-476.

- Segura Palacios JM, Boixeda P, Rocha J, et al. Laser treatment for verrucous hemangioma. Lasers Med Sci. 2012;27(3):681-684.

- Mankani MH, Dufresne CR. Verrucous malformations: their presentation and management. Ann Plast Surg. 2000 Jul;45(1):31-36.

- Baumgartner J, Šimaljaková M, Babál P. Extensive angiokeratoma circumscriptum—successful treatment with 595-nm variable-pulse pulsed dye laser and 755-nm long-pulse pulsed alexandrite laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18(3):134-137.

- Le Sage S, David M, Dubois J, et al. Efficacy and absorption of topical sirolimus for the treatment of vascular anomalies in children: A case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(4):472-477.

- Dodds M, Tollefson M, Castelo-Soccio L, et al. Treatment of superficial vascular anomalies with topical sirolimus: A multicenter case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37(2):272-277.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Yang reports no relevant financial interests.